Little Deaths and Resurrections

Embodiment is not a luxury; it’s an insistence.

Last week, I bumped into an old friend unexpectedly. After I crashed my motorcycle in 2018, he and another friend, horrified by what had happened to me, sold their motorcycles. As I hugged him, I laughed and said, "good thing we don't ride anymore." He agreed. “I just thought of you the other day” he said, “when I heard about a guy who died in a motorcycle accident.”

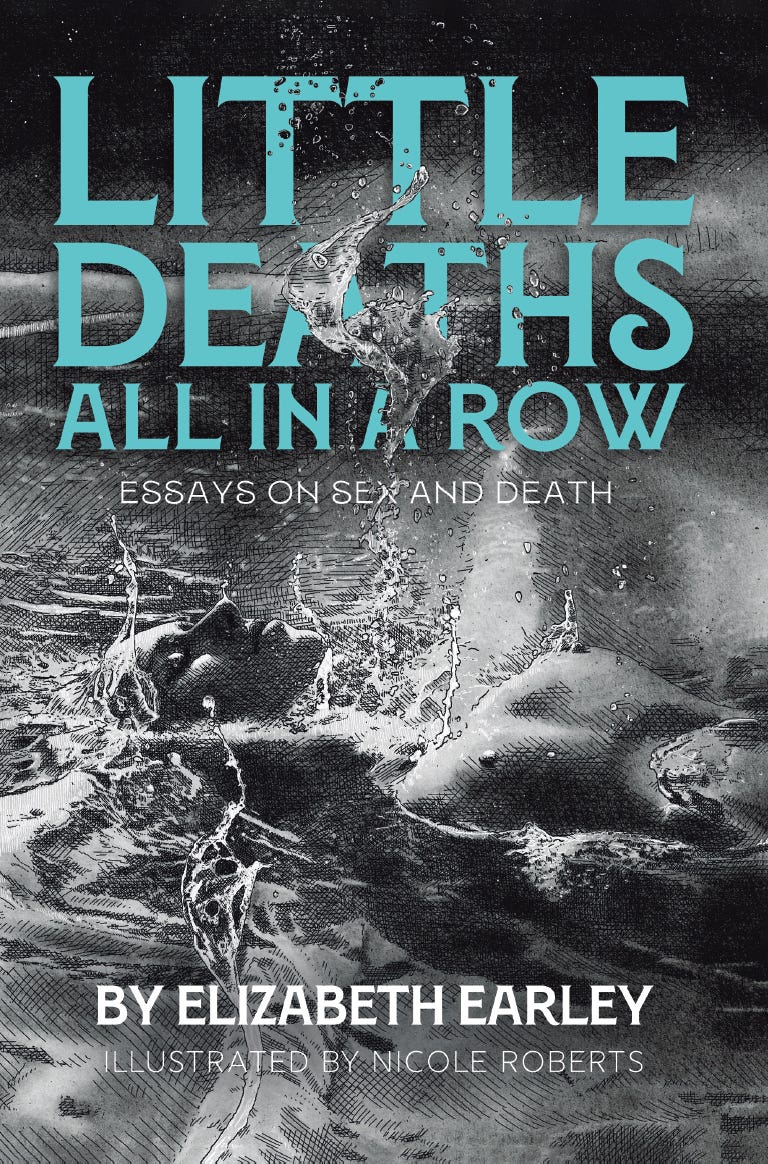

My essay collection coming out this September (Little Deaths All in a Row, Essays on Sex and Death) braids together stories and ideas surrounding seemingly incompatible experiences. I wondered, had I always linked sex together with death in my mind? Or did they tumble and tangle together only after my near fatal motorcycle accident? And why sex of all things?

There was the near death of my vagina, for one, which was connected to the near-death of my person. When my crotch slammed into the steering column of the bike, my pubic bones shattered, a shard of which cut through the femoral artery and nerve in my groin, from the inside, out through my vagina. This caused me to bleed out rapidly, lose almost all the blood in my body, and nearly die but for the transfusions I received in the ambulance. It also cut off all sensation to my genitals. The gynecological surgeon who repaired this vital artery/nerve couple in my groin gave me a 50/50 chance of ever getting the sensation back. Thankfully, after time and healing, it resurrected. Of course it did! Vaginas bounce back.

But I don't think this was the event that connected sex with death for me. Instead, it was during a previous make out session with my mortality that was less gruesome and more philosophical. A decade prior I had a cancer scare. Specialists didn’t know if this mass that had grown in my body was cancer or not until they took it out and tested it. They were calling it precancerous, and that alarmed me. Precancerous? As in, before cancer? No, they explained, it just means they could not tell for sure from the sample, so “we have to surgically remove the whole thing.”

In the interim between the precancerous determination and the surgery, I didn’t have the expected reaction, which was to pull close my loved ones and spend time with them. Instead, I wanted to be in my body and engage with my senses. I wanted to have as many purely sensual experiences as possible. The desire was overwhelming, in fact. To assuage it, I took a solo vacation and had casual sex with men.

When I learned about the show, Dying for Sex, I was anxious to see it. There isn’t much material in popular media on these topics woven together like this, and as it was so adjacent to an experience I had myself, I was curious. The show is based on the true story of Molly Kochan, a woman who, when facing her own mortality, also felt driven to have sensual and sexual experiences during whatever time she had left in her body.

Molly had a backstory that I lacked — a failed hetero marriage in which she was pitied and treated like a patient instead of desired. At its surface, the show may seem to be about reclaiming pleasure, but beneath that is a nuanced, often raw exploration of the intimate overlap between sex and death. And I was surprised at how much of it, and in how many ways, I related to her story.

The central friendship between Nikki and Molly is the emotional spine of the show. The friendship reveals how facing death can strip away shame and inhibition, allowing for a kind of radical honesty that’s rarely safe in everyday life. Sex becomes not only a rebellion against death, but a way of tasting life more fully — an insistence that the body, however temporary, still matters. Molly’s stories are filled with sensation: smells, textures, sounds. They are alive with erotic life but edged by the knowledge that life is slipping away.

What I loved most was that the series refused to offer a tidy closure. Instead, it leans into the paradox of being fully alive while actively dying. By doing so, it opens a space rarely explored in mainstream media, where death doesn’t negate desire, and desire doesn’t erase grief, but both exist together in messy, luminous truth.

I recently finished recording the audiobook for my essay collection in a studio with an audio engineer, Janine Rose. During the hours I spent reading my book to her and giving voice for the first time to my most vulnerable truths, it hit me: vulnerability is a creative force of nature. Between readings we talked and the depth of our conversations became significant. Through sharing and opening and radical truth, a friendship was created.

And this woman, my new friend, didn’t shy away from her own vulnerability — sharing with me on the same deep and open level from which I wrote this book. She is a musician and a singer/song writer, is queer, and has admirable intellect as well as emotional intelligence. She struggles with some chronic health conditions, which is one thing we have in common, and the way she described hers to me made me realize something more: how this soft animal of the body insists on the urgency of embodiment even as it fails.

In fact, it was the act of reading the essay collection aloud to her in the studio combined with her stories about her health that brought it bobbing to the surface, though it had been there all along, swimming below the riptide of the words.

The night I found myself bleeding to death on the hood of a car, I had the first panic attack of many in my life. This alone proves the concept that our mind, thoughts, and consciousness are deeply connected to and influenced by our physical body and lived sensory experience. This reminds me of this paragraph in the essay entitled “Bright Brain”:

Descartes believed the pineal gland was the source of all thoughts, though we now know that’s not true, and neural networks are that source, and such networks can be found throughout the body, including around the heart and in the genitals, but most by far are found in the brain.

When I learned of these bodily neural networks, I felt a suspicion I’d long held was finally confirmed by science — the body not only stores and hold memories but produces thoughts. It’s now scientifically sound to assert the heart, in the midst of the phenomenon of falling in love, may possibly tell the brain what to think.

Maybe it makes sense that when our bodies demonstrate their ephemerality we start connecting with and living through the body. It's the opposite of being disconnected, purely intellectual, or abstract. It's about how our body shapes and expresses who we are and how we experience the world.

In the end, sex and death are not opposites. They are both thresholds — wild, embodied, destabilizing, and deeply human. What I’ve learned, through scars and stories, through sensation and silence, is that embodiment is not a luxury; it is an insistence. It’s the body crying out, I am still here. To live through the body — especially as it falters, bleeds, or betrays — is to stake a claim in the fleeting miracle of being alive.

My forthcoming collection isn’t about answers. It’s a constellation of little deaths and resurrections, of aches and appetites, of the strange intimacy between survival and surrender. And if you listen closely — to the blood, to the nerve endings, to the voice reading aloud in a quiet studio — you might hear it too: not just a story of near-death or desire, but a body remembering itself back to life.