The Architecture of Less

The space of us is small by design so that everything inside it has a pulse.

I used to believe that abundance was synonymous with safety — more belongings, more lovers, more stories packed into the walls. But abundance can suffocate. It clutters the senses, muffles the heart. To walk into this new space of us, I had to leave behind the overstuffed drawers of past relationships, the artifacts of grief and betrayal that weighed more than they gave. The closets I once closed so tightly against myself, so no one could see how much I carried, how much I couldn’t put down.

And then there was you. There was the way our gravity recognized itself. The pull was not subtle. It was the quiet certainty of something that had always existed, subterranean, waiting for us to step into it.

When I met you and we touched for the first time, I sensed that whatever came next, it would not be trivial. Your home was small, most of your things still in storage, you said. Later, you moved into a larger loft apartment with soaring ceilings and took everything out of storage for the first time in years, even adding new items to fill the bigger space. Meanwhile, I had expanded into my own house where I’d moved years earlier, with a closet as big as my previous bedroom had been. Now, you’re packing to move some things back into storage and other things into a smaller space that you will share with me, and it seems metaphorically potent.

Love, as I have come to know it, is not the sprawling house with echoing halls and guest rooms we never enter. It is the smallish apartment with floor-to-ceiling windows, a place that teaches us to live only with what matters. A smaller space, stripped of redundancy, where every object earns its keep. At first glance, downsizing looks like loss: fewer closets, fewer surfaces to decorate, fewer corners to hide inside. But once we begin shedding, the paradox reveals itself. In less, we discover more. More light, more air, more intimacy. A clarity that larger spaces, with their cavernous indulgences, cannot offer.

On our second date, I did the most reckless and most honest thing I have ever done in love: I asked you to illustrate my book. Little Deaths All in a Row: Essays on Sex and Death. Even its title was a naked thing. The most vulnerable manuscript I had ever written, the marrow of me laid out on paper. I knew that showing it to you would either draw us closer into a single orbit or send you running. It was a test, though not of you —of me. Could I love someone enough to let them see all of it? The brokenness, the strangeness, the brutal honesty? I felt, even then, that the stakes were everything.

And when you said yes, I glimpsed the outline of what we could be. Not just lovers but co-conspirators. A creative duo, a power couple not in the shallow sense of ambition, but in the deeper sense of what happens when two artists choose to risk together. To put their names side by side on a spine, to marry vision with vision. It was the beginning of us as architects of something larger than either of us could make alone.

But to build it, we had to strip away what was not necessary. To resist the temptation to fill the space with excess. Like downsizing into a small apartment, we made choices: this we will carry forward, this we will leave behind. No dead weight. No half-hearted belongings. The space of us is small by design so that everything inside it has a pulse.

Pain, too, has taught me this economy. The body needs its limits. Pain is the signal that keeps us alive. Without it, the child who cannot feel will rest her hand on the stove until it is ruined. She will not know that an infection has spread until it has already claimed too much. Pain is not cruelty — it is boundary. It is the body insisting on what cannot be endured.

So too with the heart. The pain of my past — of rooms too cluttered with betrayal, of drawers too heavy with unsaid words — has become my map. Each ache a red line across my palms, instructing me where not to return. Without those lessons, I would not know how to choose differently. Without the sting of what was unsafe, I might mistake danger for love again. Pain is what has allowed me to arrive here, in this space that looks small but is flooded with light.

And this is what I mean when I say love is like downsizing. To be here with you, in this deliberate space, is to feel the paradox of freedom born from constraint. The fewer belongings we carry, the more room there is for breath. The smaller the floorplan, the larger the windows seem. Each object is sacred because it survived the culling. The bed is not just where we sleep but where we learn the syntax of each other’s skin. The table is not just for eating but for returning, daily, to the practice of communion. There is no junk drawer in this love. There is nothing forgotten or tolerated out of habit.

What we make together — on the page, in the world, in the space between our bodies — depends on this discipline. To choose only what matters. To trust the pull that has always been there. And still, sometimes, I marvel at it. That second date. That impossible question I asked. The way my hands trembled even as I placed my most vulnerable work into yours. I did not know if I was risking everything or beginning everything. But maybe those two are the same. Maybe all beginnings worth keeping arrive with the possibility of annihilation.

What I know now is this: we built a life inside the paradox. Smaller, but freer. Boundaried but more expansive than anything I could have imagined. Every belonging, every page, every word between us matters. And when the light pours in, I see that what looked like less from the outside is actually the most I have ever had.

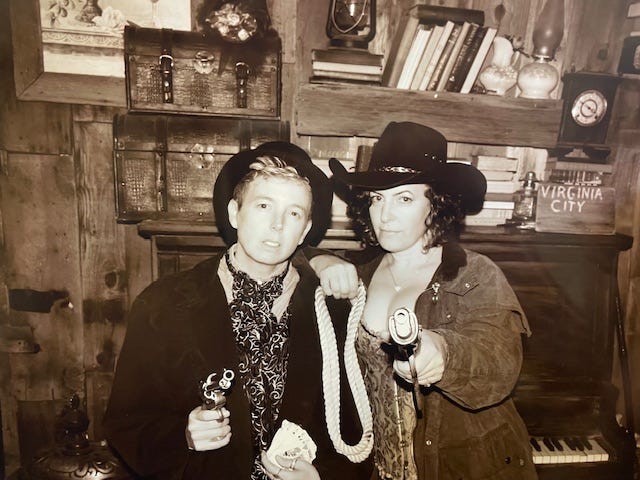

Photo description: El and Nicole in Virginia City during their first year together taking a themed photo dressed up as bank robbers.

What a wonderful realization and love letter. Thank you for taking the risk to be vulnerable with your truth and writing.

This is so beautiful. Thank you for sharing.