The Dualities within Us and the World Today

How wide will the pendulum swing?

I’ve been reading my first novel aloud in a recording studio for the audio book, which I’m finally making only now, more than a decade after it was published.

The novel is based on an earlier version of me, my younger self and her life, her family of origin, her alcoholism and drug addiction, which feel so distant now. It’s a strange experience to revisit that time and that version of me — it’s like a past life that I kind of sort of remember. In fact, it’s brutal.

It’s clear to see from my perspective here, now, how much was about survivor’s guilt. When I was ten, my older sister suffered a tragic, near-fatal car accident as a new driver at age sixteen. How I believed I should have been the one who “deserved” that senseless tragedy, not her. She was the better person: smarter, kinder, more altruistic. I was devious and dark, a liar and a thief. My guilt about surviving was so big that I tried in earnest to destroy myself. It’s shocking that I didn’t succeed.

I got sober rather young, but I didn’t feel young, and in that short amount of life I had managed to inflict a tremendous amount of damage and pain. Inside, I was fractured, split — there was a wounded child who lost cherished protectors and caregivers too young and developed maladaptive ways to take care of herself in the world (lying and stealing); and a newly minted adult with tight buds of unrealized maturity and wisdom promising to open, to bloom, so long as the sunlight of sobriety was allowed to reign consistently henceforth. That light did remain, but shadows were ever present, and what lurked inside of them seemed threatening and strong.

Fast forward twenty-five years: I find myself still miraculously sober and thriving, having jumped the track on self-destruction and diverted the trajectory of my life toward that opening, blossoming growth my young adult self felt the promise of so long ago. And yet, I am living this life now inside of a human family more divided than ever.

We have a devastating president of our country, a blatant criminal unpunishable by law. More than half of us always knew that this person was a felonious, cheating, narcissistic (or psychopathic) rapist, pedophile, and the least of all, not qualified to scrub toilet bowls at a rest stop on the highway much less lead the country. And now this axis of evil has returned, implanting a regime to enact state-sanctioned ethnic cleansing in this country, deploying masked men to kidnap innocent people off the streets and from their homes, cars, workplaces and immediately deport them to prison camps in countries they have never known and will never be able to escape from.

The regime is also attempting in earnest to impoverish the majority of our citizens and strip them of their healthcare, destroying academia and education so people become even easier to control, casting many thousands of people around the world into starvation, sickness, suffering, and death, while waiting food and medicine rots in warehouses.

I have watched this political pendulum swing in my lifetime, and each time the swing goes wider. When Obama won a second term, and I celebrated because I disliked Romney and his now seemingly mild misogyny. A friend slowed my roll. I was confused.

“Why aren’t you dancing with celebration?” I asked.

“What happens when you push on a dog?” she asked. I was silent but understanding dawned. It’s the law of push and push back. He’s winning now, but this might mean the next president will be the devil. She was right.

What frustrated and enraged me during the election in 2024 was how many people were unwilling to vote for Kamala because of the administration’s support of Israel and their spite about that. Understandable. Still, the Biden administration had at least shown willingness to engage in some kind of peaceful diplomacy and hear grievances. Withholding that vote or voting for the other side was electing instead the blatantly anti-Muslim, eager to help Israel complete its project of genocide, entertaining the possibility of turning Gaza into the next Mar-a-Lago Club.

So hey, guys, great work with your protest vote.

And yes, the pendulum will swing again, and it will swing hard, and maybe that will mean that our next president will be a Black trans woman who will outlaw cis gendered maleness in this country. But what about when it swings again? Maybe it’s goodnight humanity at that point.

One of my favorite novels is East of Eden by John Steinbeck. What I love about it is how Cal Trask embodies the capacity for both cruelty and goodness. He has a deep desire to be loved, yet torment comes from the feeling that he is inherently bad (I so relate to this character).

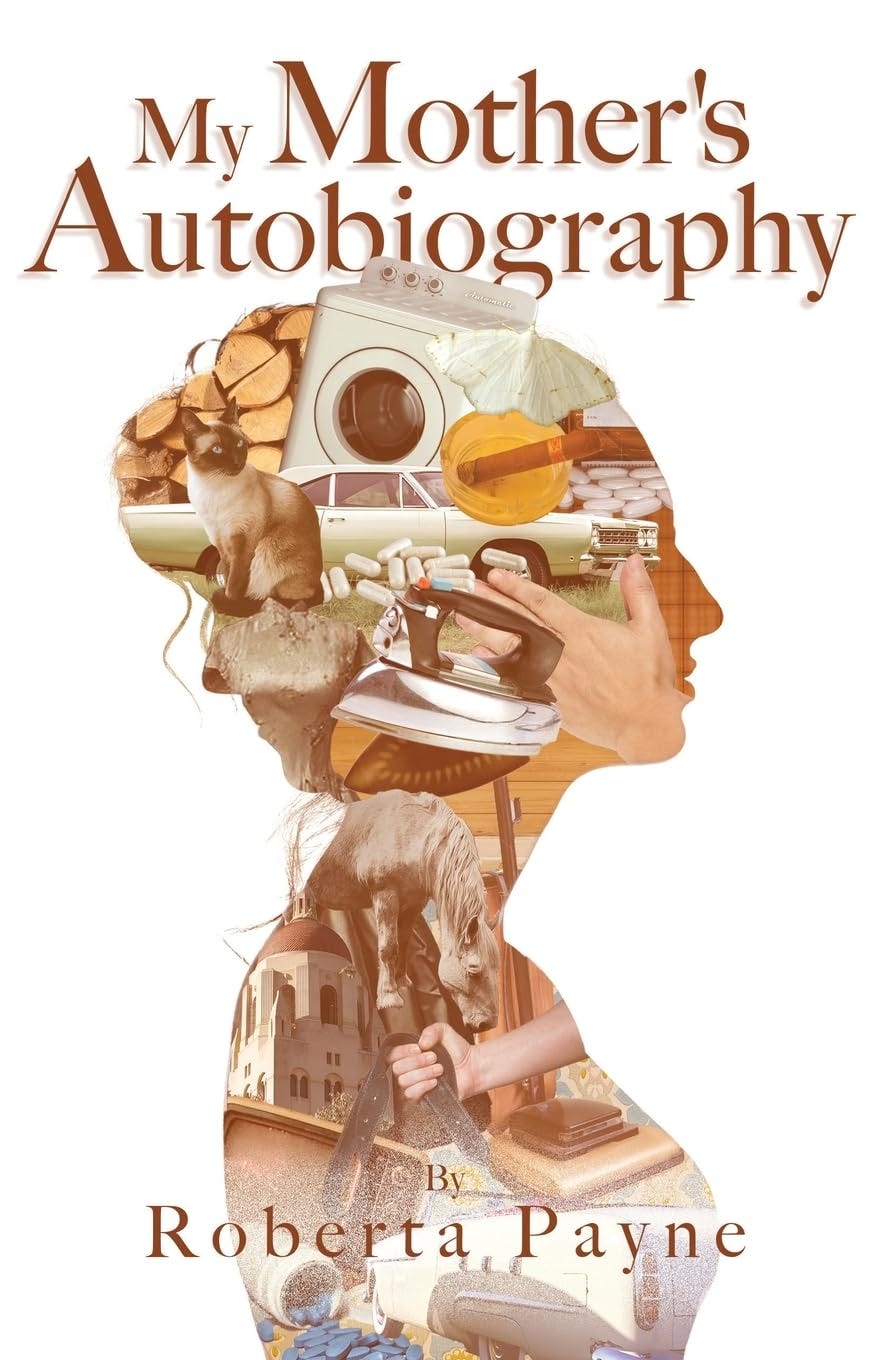

In My Mother’s Autobiography by Roberta Payne, another great novel, the mother character is torn between roles of woman, mother, addict, seeker — the “good” versus “fallen” woman archetypes from 1950s America. Like Cal and Adam Trask in East of Eden, this mirrors the Cain and Abel good and evil dichotomy. Addiction is both her self-destruction and her strategy for survival (I so relate).

Steinbeck’s philosophy of timshel (free will to choose good or bad) aligns deeply with recovery work: the power of choice in the face of overwhelming generational pain and trauma. Roberta Payne’s narrative echoes this. Choice is both a privilege and a burden when one's psyche is torn by mental illness, societal judgment, and addiction.

East of Eden was written by a man, and Cathy is a vilified mother/temptress figure. Looking back at the novel through a feminist lens, I question this framing and how women are allowed (or not allowed) to contain multitudes. My Mother’s Autobiography offers a feminist corrective — instead of flattening a woman into monster or martyr, Payne’s mother character is complex: loving and unstable, brilliant and broken. Her story becomes a reclaiming of moral and narrative agency.

What does all this have to do with my own life’s trajectory and the light and the dark of it? Nothing really, but also everything. We live in a relative world with duality as one of the fundamental laws of nature. Can we look to the dueling dualities within us and how we reconcile those for a clue as to how we might collectively handle what’s happening in the world around us today?

Toni Morrison famously wrote about the ways humans instinctively self-segregate and “other” those who are different. One of her most powerful explorations of this comes from her 1990 Harvard William E. Massey Jr. Lecture, later published as the essay Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. In it, she examines how American literature constructs the category of the "other" — particularly Blackness — as a means of shaping white identity, often by exclusion or marginalization.

Even more directly, in her lectures (notably “Hard, True, and Lasting,” University of Miami, 2005), Morrison crystallizes this human tendency. “And the question . . . Even when it is not spoken, this deep and psychic struggle going on to see and not see the other? Exactly.” The impulse to split the world into "us" and "them" is not only social or cultural — it’s a psychological act, one that is so destructive it becomes pathological.

Yes, we live by duality — the push and pull of light and dark, the pendulum ever swinging. But must it always swing wider, more violently with each pass? Maybe not. Maybe, over time, the arc softens.

I’ve seen this in my own sober life, where the extremes have quieted; where light and shadow no longer wage war but coexist, even harmonize — not perfectly, but with a kind of hard-won grace. I don’t expect utopia, and I don’t need it. But I do want to believe — even just a little — that humanity, like the self, can learn to integrate, to balance, to heal. Maybe not completely, maybe not all at once. But even that small movement toward wholeness is worth hoping for. And worth working for.

Cover art by Nicole Roberts